8

By taking a couple of courses in economic theory, we could immunize ourselves from nonsense spouted by politicians and pundits, but in the meantime check out Professor John R. Lott's "Freedomnomics: Why the Free Market Works."

His first chapter is "Are You Being Ripped Off?" It addresses myths about predation where it's sometimes alleged that corporations will charge below-cost prices to bankrupt their rivals and then charge unconscionable prices. There's little or no evidence that corporations would choose predation as strategy; there are too many pitfalls. A major one is that in order to recoup losses from charging low prices to bankrupt rivals, the predator would later have to charge higher-than-normal prices. That would attract new rivals who might have purchased the bankrupt assets of the predator's prey and be able to undercut the predator's prices.

A far more successful means to monopoly wealth is for businesses to enlist the aid of congressmen to form a collusion. Classic examples are the dairy industry, which uses the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Federal Milk Marketing Orders to set statutory minimum prices, or the Gasoline Retailers Association using state law to do the same or the sugar industry using Congress to establish quotas on foreign sugar imports.

Professor Lott's chapter "Government as Nirvana" highlights examples of government predation. When the U.S. Postal Service raised the price of first-class mail in 1999, it reduced its price for domestic overnight express mail from $15 to $13.70, even though it was losing money at $15. The Postal Service was facing stiff competition from FedEx and UPS overnight services and wanted to keep its market share.

During the 1980s, private meteorology firms saw a chance to make money by selling television stations specialized forecasts that weren't provided by the National Weather Service. The National Weather Service started providing television stations the same services for free, thus driving private forecasting companies out of business.

Predation is observed in higher education. UCLA is both Lott's and my alma mater. It spends $40,000 per student but charges $6,522 tuition for in-state students. Such below-cost pricing gives public universities a significant competitive advantage over private universities. State universities have acquired many formerly private universities after driving, or threatening to drive, them out of business. Lott gives examples of George Mason University School of Law, University of Buffalo, University of Houston and University of Pittsburgh. In the case of University of Buffalo, the State University of New York reportedly threatened to open a public university across the street unless the University of Buffalo joined the state system.

The U.S. Department of Justice would go after a private business using similar predatory practices of intimidating its rivals and selling goods and services below cost. The U.S. Department of Commerce sanctions foreign companies accused of selling goods in the U.S. below cost with anti-dumping duties. If selling goods below cost is seen as unfair in the international arena, why is it not when it's done by government entities?

Lott's "Crime and Punishment" chapter has a lot of interesting tidbits. It starts off stating a fundamental principle of economics: the higher the cost of something, the less people will do of it. To demonstrate the generality of this principle, Lott says that when the number of referees were increased from two to three in the Atlantic Coast Basketball Conference, fouls fell by 34 percent; fouling became more costly. The American League has more hit batsmen than the National League, but the difference only appeared after 1973 when the American League removed its pitchers from the batting lineup in favor of designated hitters. Not being afraid of being hit themselves, American League pitchers threw more bean balls; bean balls became cheaper. The same principle applies to the U.S. crime rate that fell after the death penalty was reinstated, more prisons were built and concealed-weapon carry laws were enacted. The higher the cost of a crime, the less people will do of it.

China Is Exerting A Destabilizing Influence As The Balance Of Economic Power Shifts

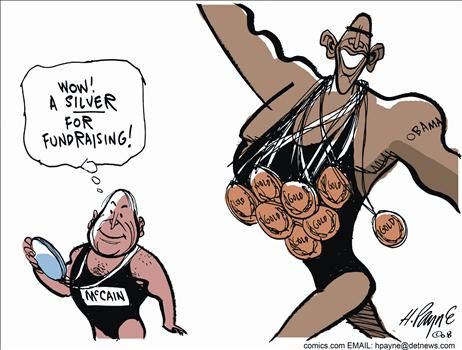

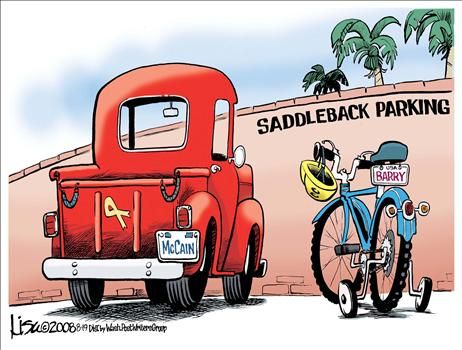

Obsessed with rankings, Americans are bound to see the Beijing Olympics as a metaphor for a larger and more troubling question: Will China overtake the U.S. as the world's biggest economy?

Well, stop worrying. It almost certainly will. China's economy is now only a fourth the size of the $14 trillion U.S. economy. But given plausible growth rates in both countries, China's output will exceed America's in the 2020s, projects Goldman Sachs.

But this is the wrong worry. By itself, a richer China does not make America poorer. Indeed, because there are so many more Chinese than Americans, average Chinese living standards may lag behind ours indefinitely. By Goldman's projections, average American incomes will still be twice Chinese incomes in 2050.

The real threat from China lies elsewhere. It is that China will destabilize the world economy. It will distort trade, foster huge financial imbalances and trigger a contentious competition for scarce raw materials.

Symptoms of instability have already surfaced, and if they grow worse, everyone — including the Chinese — may suffer. China is now "challenging some of the fundamental tenets of the existing (global) economic system," says economist C. Fred Bergsten of the Peterson Institute.

This is no small matter. Growing trade and the cross-border transfers of technology and management skills contributed to history's greatest surge of prosperity. Living standards, as measured by per capita incomes, have skyrocketed since 1950: up 10 times in Japan, 16 times in South Korea, four times in France and three times in the United States.

Significantly, these gains occurred without serious political conflict. With the exception of oil, world commerce expanded quietly. The chief sources of global strife have been ideology, nationalism, religion and ethnic conflict.

Economics could now join this list, because the balance of power is shifting. The U.S. was the old order's main architect, and China is a rising power of the new. Their approaches contrast dramatically.

Economically dominant after World War II, the U.S. defined its interests as promoting the prosperity of its allies. The aims were to combat communism and prevent another Great Depression. Countries would make mutual trade concessions. They wouldn't manipulate their currencies to gain advantage. Raw materials would be available at nondiscriminatory prices.

These norms were mostly honored, though some countries flouted them (Japan manipulated its currency for years).

China's political goals differ. High economic growth and job creation aim to raise living standards and absorb the huge rural migration to expanding cities. Economist Donald Straszheim of Roth Capital Partners estimates the urban inflow at about 17 million people annually.

As he says, China sees export-led growth as a magnet for foreign investment that brings modern technology and management skills. Prosperity is considered essential to maintaining public order and the Communist Party's political monopoly.

At first, China pursued its ambitions within the existing global framework. Indeed, the U.S. supported China's membership in the World Trade Organization in 2001. But as it grows richer, China increasingly ignores old norms, Bergsten argues. It runs a predatory trade policy by keeping its currency, the renminbi, at artificially low levels.

That stimulates export-led growth. From 2000 to 2007, China's current account surplus — a broad measure of trade flows — ballooned from 1.7% of gross domestic product to 11.1%. The biggest losers are not U.S. manufacturers, but developing countries whose labor-intensive exports are most disadvantaged.

Next, China strives to lock up supplies of essential raw materials: oil, natural gas, copper. If other countries suffer, so what? Both the United States and China are self-interested. But the U.S. has seen a prosperous global economy as a means to expanding its power, while China sees the global economy — guaranteed markets for its exports and raw materials — as the means to promoting domestic stability.

The policies are increasingly on a collision course. China's undervalued currency and massive trade surpluses have produced $1.8 trillion in foreign-exchange reserves (China in effect stockpiles the currencies it earns in trade). Along with its artificial export advantage, China has the cash to buy big stakes in American and other foreign firms.

Predictably, that has stirred a political backlash in the U.S. and elsewhere. The rigid renminbi has contributed to the euro's rise against the dollar, threatening Europe with recession. China has undermined world trade negotiations, and its appetite for raw materials leads it to support renegade regimes (Iran, Sudan).

The world economy faces other threats: catastrophic oil interruptions, disruptive money flows.

But the Chinese-American schism poses a dilemma for the next president. If we do nothing, China's economic nationalism may weaken the world economy — but if we retaliate by becoming more nationalistic ourselves, we may do the same. Globalization means interdependence; major nations ignore that at their peril.

Kudos For Carter

Trade: Never thought we'd say this, but Jimmy Carter finally got something very right. From Plains on Sunday, he urged Congress to pass the free-trade pact with Colombia. Fellow Democrats should take heed.

It was good to see President Carter assuring Colombian President Alvaro Uribe that he'd "prudently but effectively" try and persuade Congress to end its moratorium on free trade with Colombia. On his Web site, Uribe said Carter's help "is going to be very useful."

Along with offshore drilling, Colombia's treaty has languished in Congress without a vote since April. Speaker Nancy Pelosi altered House rules to block a vote — and to advance Big Labor's agenda.

Although the Carter Center called the Uribe meeting a private visit and said Carter made no public statement, Carter's stance echoes one of the few bright spots of his failed 1976-1980 presidency — his willingness to confront protectionists and help local markets.

In 1977, he fought off shoe tariffs and lashed out at special interests. He's since been a booster for Atlanta as a center for Latin trade, a savvy thing since U.S.-Latin trade grew 19.7% in 2007. So, it's not out of character for Carter to help on the Colombia pact.

But it's still worth noting because he's going against the trend.

Big Labor's cash controls the Democrat-led Congress, leaving many Democrats cowed on free trade. So, there's probably little political gain for Carter to support free trade.

It also may be a sign the Democratic Party is softening on free trade, too. Much, after all, has changed since Pelosi's roadblock.

• In July, Colombia made a daring rescue of three U.S. hostages held by terrorists, putting its own men in harm's way to save ours.

• Colombian troops also captured a massive trove of intelligence from a terrorist leader's computer last March, and shared the bounty with us. Its friendship isn't in question.

• Colombia's now the U.S.' fastest-growing Latin American trading partner. A Latin Business Chronicle analysis shows $12.2 billion in U.S.-Colombian trade in the first half, up 54% from the same period last year. But U.S. exporters still pay duties, undermining the market. Free trade will fix that.

• Meanwhile, Russia's invasion of Georgia sent a warning that unprotected U.S. allies are easy targets for predators. Free trade also would cut the power of Venezuela's petrodollars by helping Colombians and others in the region to grow more prosperous.

Carter hasn't been right on many things, but he's on target on free trade for Colombia and others in Latin America. He deserves some credit for finally doing something useful.

No comments:

Post a Comment