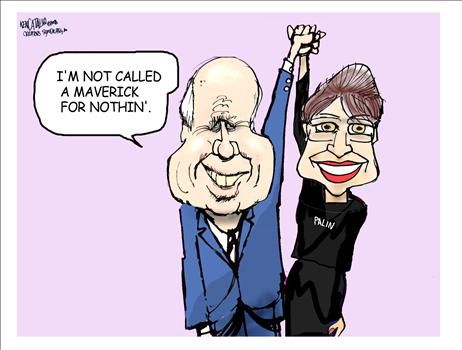

John McCain's running mate

Palin to significance

John McCain makes the surprise choice of Sarah Palin, governor of Alaska, as a running mate

NEVER let it be said that politics deals no surprises. After weeks of speculation about his choice for vice-president on the Republican ticket, John McCain bypassed the names most often mentioned, such as Tim Pawlenty and Mitt Romney. On Friday August 29th he chose a little-known candidate—Sarah Palin, governor of Alaska for less than two years.

Ms Palin is the first woman on a Republican ticket; by selecting her the McCain campaign will hope to expand its reach to female voters, though she may be a tough sell to disaffected supporters of Hillary Clinton. Born in small-town Idaho, Ms Palin moved to small-town Alaska when she was a child. She is a former beauty queen and a keen sportswoman—her aggressive style of playing basketball earning her the nickname “Sarah barracuda”. As a mother of five she will be able to empathise with other hard-pressed female professionals balancing home and career.

Opting for Ms Palin may also go some way towards soothing the nerves of social conservatives, who were aghast at Mr McCain’s recent suggestion that he would not necessarily rule out picking a vice-president who supports abortion rights. Mr McCain may have heeded the warning that such a selection would cause “the base” to stay at home on election day; one poll found that 20% of McCain supporters would be less likely to vote for him if his veep was pro-choice. But Ms Palin is a staunch Christian, a member of the National Rifle Association, and enjoys fishing and hunting.

Although she is popular with conservatives, Ms Palin will not be able to cement the evangelical wing of the party to Mr McCain in the same way that the selection of Mr Pawlenty would have done through his strong ties to the National Association of Evangelicals.

But the risks of choosing such an unknown quantity are enormous. An important aspect in selecting a vice-president is to reassure the electorate that should anything happen to the man in the Oval Office there is a competent and trustworthy stand-in ready to take over. John McCain’s age (he is 72) is an underlying factor with voters. Although Ms Palin’s youthfulness, she is 44, is an eye-catching contrast to the top of the ticket, questions will be raised about her ability to run the country if Mr McCain should ever be incapacitated.

And the tenures of both Al Gore and Dick Cheney as vice-president have raised the profile of the office. Vice-presidents were once expected to be solid and reliable but mostly boring. Messrs Gore and Cheney took on policy portfolios, such as government reform or preparing for war with Iraq. Barack Obama’s pick of Joe Biden for the role now seems all the more wise.

By choosing the governor of Alaska as his running mate, Mr McCain also turns the spotlight on the state’s politics, which is currently entangled in corruption scandals. Ted Stevens, the longest-serving Republican senator ever, faces corruption charges in relation to building work on his home. Other state officials are under investigation in separate cases. And Alaskans are going through a period of introspection about politics and energy interests, on which the state has thrived.

Mr McCain lauded Ms Palin's “record of delivering on the change and reform” needed in Washington, DC, and clearly recognises her as a fellow maverick. She was elected as Alaska’s youngest ever governor in 2006, a bright spot in a dreadful year for the Republican Party, which lost control of Congress in the mid-term elections. She arrived in Juneau, the state capital, with a squeaky-clean agenda, vowing to reform the state’s politics and root out corruption. She built a reputation for taking on the state's big oil interests with their links to the Republican Party. However, Ms Palin has become embroiled in a minor scandal concerning the sacking of a state trooper, though she adamantly denies any wrongdoing. The state legislature is now investigating the whole affair, to Ms Palin’s embarrassment.

Still, come Monday and the start of the Republican convention in Minneapolis-St Paul, there will be a new star in the Republican firmament. Whether she will help or hinder Mr McCain’s campaign against Barack Obama is far from clear.

Russia's propaganda warfare

| By William Horsley European affairs analyst |

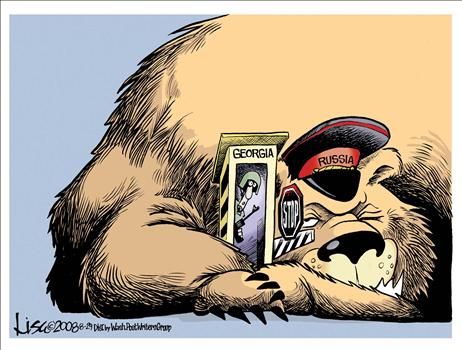

Western leaders face two fronts in their stand-off with Russia over its use of force to re-draw borders in Europe: one is the Russian army on the ground. The other is a propaganda war.

Russia's defence of its intervention has not always been convincing |

Meanwhile, Russia has unleashed a propaganda barrage against an "aggressive" Nato alliance, drawing sharp ripostes from western leaders.

President Dmitry Medvedev, who came to office with overtures to the West, now warns of a "crushing response" to any other country that threatens the lives or dignity of Russian nationals. He is "not afraid of a new Cold War", he adds.

Inconsistencies

This war of words is not just a diversionary tactic.

The statements of Russian leaders reveal an underlying strategy which suggests that the West is right to see dangers ahead from the actions of a belligerent Russia.

| |

But those same statements also show glaring inconsistencies which belie Russia's apparently strong hand.

The Russians' strongest argument in defence of its armed intervention is that blame for the outbreak of a shooting war is shared.

Most observers agree it is, and that Georgia's President Mikheil Saakashvili acted rashly or wrongly in ordering his army to bombard and take the South Ossetian capital Tskhinvali.

He was wrong, too, to speak of Russia "exterminating" his nation.

But in many other ways, Russia's defence of its armed intervention has been found wanting or false.

Russia's official charges of "genocide" by Georgian forces against the South Ossetians were quickly discredited by Human Rights Watch.

Broken promises

Moscow's South Ossetian allies still claim that nearly 1,700 people died in the Georgian assault but evidence has yet to be produced.

Moscow's repeated promises to withdraw its forces as prescribed in the French-brokered ceasefire plan have been broken in many parts of Georgia.

|

That is what prompted the European Union and Nato to accuse Moscow of breaking international law, and breaking its word.

Mr Medvedev argued that Russia had been forced to use force to protect its own nationals in South Ossetia.

But Russia has deliberately engineered that situation by handing out Russian passports to large numbers of local inhabitants.

Sweden's normally soft-spoken Foreign Minister Carl Bildt retorted that Russia's resort to that argument echoed that of Hitler in annexing pre-World War Two Czechoslovakia.

Finally, Russia's claim that its motive in Georgia was purely humanitarian was exploded by this week's decision to recognise the independence of the two breakaway regions.

This catalogue of feints and deceptions has hardened international opinion towards Russia to the point where the West is undertaking an overall review of ties with Moscow - something scarcely imaginable only a month ago.

The acute international alarm regarding Russia stems from the offensive part of its concerted campaign to send messages of varying degrees of threat to other countries.

Strategic target

Dmitry Medvedev's hint that Russia might feel justified to intervene on behalf even of Russians living in other states brought a defiant show of solidarity from the leaders of Ukraine, Poland and the three Baltic states as well as Georgia.

The fall-out from the Georgia conflict may prove disastrous for Russia |

A senior Russian commander explicitly threatened Poland - saying it made itself "100%" into a Russian strategic target - after the Poles signed an agreement with the US to station American troops and missile defence shield interceptors on its soil.

Russia's Deputy Foreign Minister Grigory Karasin castigated the western media for what he called their consistently anti-Russian reporting of the Georgia conflict.

But in Europe's free and diverse media Russia's side of the story is regularly reported in detail, and views critical of the US over Iraq and Kosovo are commonplace.

In Russia, by contrast, the most influential medium of TV is heavily slanted to favour the Kremlin's line.

Catastrophic

Russia's plea for understanding is undermined by its various punitive actions over recent years against nearly all of its neighbours to its west, from cutting the flow of gas to Ukraine to alleged cyber-attacks against Estonia.

Russia does indeed have friends in the West who are inclined to take a lenient stance now - Italy's Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi for one, who once put himself forward as Vladimir Putin's "defence lawyer".

But the real international fallout from Georgia is proving little short of catastrophic for Russia.

By its actions it has put at risk its privileged position within the G8, and earned the clear condemnation of Europe's two major international institutions devoted to building democracy and peace - the Council of Europe and the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe.

A way out for Russia lies in the precise pledge made by Mr Medvedev when he became president of Russia only three months ago - that he would strive to make Russia a nation that truly respects the rule of law and international norms.

Otherwise Russia could be undone by its own myths, and be isolated in the new Cold War that its leaders still say they do not seek.Commentary by William Pesek

Aug. 29 (Bloomberg) -- So, the dollar isn't on its own.

That's the upshot of a Nikkei newspaper scoop yesterday that European, Japanese and U.S. officials in mid-March drew up plans to strengthen the U.S. currency following troubles at Bear Stearns Cos. Assuming the report is correct, such an effort might be dubbed ``The Committee to Save the Dollar.''

It would be the currency-market equivalent of the ``The Committee to Save the World.'' That term was coined in February 1999 by Time magazine when it splashed Alan Greenspan, Robert Rubin and Lawrence Summers on its cover. Time credited them with ending a global crisis that began in Thailand in July 1997.

Thailand, of course, is again in a state of chaos. Yet the eyes of the world haven't been on the Thai baht this year, but a dollar seemingly in freefall. In July, the dollar declined to $1.6038 per euro, the lowest since the euro's inception in 1999.

That was then. The euro is down 9 percent versus the dollar since mid-July, making any meetings of the Committee to Save the Dollar, or global moves to intervene in markets, less necessary.

``The risk would appear to have diminished as markets have come to realize that Europe's economy is weakening,'' says Paul Donovan, deputy head of global economics at UBS AG in London.

Japan's is slowing, too. The world's second-largest economy contracted an annualized 2.4 percent last quarter, raising the chances of a recession. Weakening growth also increases the odds the Bank of Japan will cut its 0.5 percent benchmark rate.

Why Now?

The dollar isn't doing better because the U.S. outlook is brightening. Rather, economies -- such as Japan's and those in the euro area -- that were forecast to hold their ground are losing pace. The Federal Reserve, meanwhile, isn't expected to cut rates with the U.S. consumer-price index up 5.6 percent for the 12 months ended in July.

The thing about the Nikkei's unnamed-source story is that it was both surprising and utterly predictable. It was surprising because it had traders wondering why officials would leak such news now. Why not three months ago when the dollar was sliding?

One possibility is that policy makers want the dollar's recovery to continue. Knowledge of an agreement to stabilize markets, says Naomi Fink, a senior currency analyst at Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ Ltd. in Tokyo, ``could be a disincentive for runaway dollar-selling speculation.''

Credit Crisis

The report was also predictable because, well, one would hope policy makers were mulling responses to the dollar. That may be what Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke was trying to convey in June when he said the central bank was ``attentive'' to the currency's effect on inflation expectations. Central bankers never mention exchange rates casually.

Many were equally attentive to how the dollar's drop was helping to boost oil prices. Commodity-price inflation makes it difficult for Asian central banks to cut interest rates to support growth. The quickest solution is to stop the dollar from falling, a dynamic that might reverse the increase in oil prices.

None of this means the dollar won't plunge anew if the global credit crunch worsens. For the moment, though, the need for some kind of Plaza Accord-like currency deal has been reduced. That's good news for nations concerned that further declines in the dollar will shake up the global economy.

Asia's problems run deeper than the dollar. Between slowing growth, inflation, political instability and troubles in credit markets, economic officials have their hands full.

Pakistan's Woes

Nowhere is that truer than Pakistan, which yesterday imposed emergency trading limits to halt a slide in stocks that sent the benchmark index down 42 percent since April. It was the second attempt in two months to restore confidence in a market battered by political upheaval, and it's unlikely to help.

A rigged market wouldn't work for a stable economy, never mind one rocked by a political crisis. Far from restoring calm, the ouster of President Pervez Musharraf and the breakup of the coalition government have only spooked investors.

Should fresh turmoil flare up elsewhere, markets will be looking out for assertive actions from the biggest economies.

According to Nikkei, the March plan would have the U.S. Treasury Department, Japan's Finance Ministry and the European Central Bank directing the purchase of dollars and the sale of euros and yen. Japan would provide the yen needed for currency swaps if the dollar dropped significantly.

The three groups, which considered making an emergency statement through the Group of Seven industrialized nations, didn't stipulate a specific exchange rate for the potential move, nor did they detail how much money would be used, Nikkei said.

The good news is that such a plan probably exists. The bad news is that there's no guarantee the Committee to Save the Dollar will be able to rescue it.

Commentary: Palin is brilliant, but risky, VP choice

By Ed RollinsEditor's note: Ed Rollins, who served as political director for President Reagan, is a Republican strategist who was national chairman of Mike Huckabee's campaign. For a rival view of the Palin pick, read here.

Ed Rollins says Sarah Palin has a compelling story and has immense potential to attract women voters

NEW YORK (CNN) -- John McCain's brilliant but risky "Hail Mary pass" choice for vice president, Alaska Gov. Sarah "Barracuda" Palin, has the political world saying first: Who? And then: Why?

The "who" is a young, articulate, smart, tough, pro-life woman who is the governor of our northernmost state. She is conservative and a mother of 5, including a son in the Army who is set to be deployed to Iraq on September 11. Her youngest child has Down syndrome.

The "Barracuda" nickname came from her aggressive basketball play on the state championship basketball team. She is a hunter, pilot and lifetime member of the NRA.

She is blunt, outspoken and charming. And don't assume she can't stand toe-to-toe with Joe Biden. She is a great debater. And she was runner-up for the Miss Alaska title, won Miss Congeniality in that contest, and plays the flute.

She also has a compelling story and is a most interesting choice. She will be known by all in 24 to 48 hours in this instant media world and I am betting she will be well-liked.

The "why" is she is a governor and outside the Beltway. Conservatives love her and she shares John McCain's value system. She is also known for taking on the establishment and ethics is her forte.

She defeated the longtime senator and Republican governor in a primary and then went on and defeated the former Democratic governor.

I don't believe people vote for vice president but only for president. That said, I think she is every bit as good a choice as Biden. Alaska has three electoral votes and so does Delaware -- so that part ends up being a wash.

I think the potential for her to attract women voters is immense. And I am betting, win or lose or draw, she is a future star of a party in desperate need of young people and women role models.

And by the end of this campaign, she too will be a celebrity and her life will never be the same again. I hope that's all for the good.

Speaking of celebrities, Barack Obama proved why he is one at INVESCO Field, home of the Denver Broncos, last night before 85,000 crying, cheering adoring fans. And what's wrong with that? He is a real talent and he excites and inspires his supporters.

Those of us who are not supporters need to step back and quit watching in awe and prepare for battle. Obama's natural and developed speaking style is unchallengeable.

I've been in politics for 40 years. I had the privilege of serving Ronald Reagan as his White House political director and campaign manager and during those years I heard him give hundreds of speeches

And no one was ever better. His words enlightened, gave comfort, inspired and made Americans feel good about themselves again. He also had a core of beliefs developed over a long period of time that led to a very effective agenda.

The Democrats now have their own version of an RR orator. And, like Reagan, Obama's speeches are his own words. Whether he will be elected president or will have the accomplishments RR did only time will tell. But his gifts of speech and ability to inspire his supporters are impressive and should not be underestimated.

Saying all that, and putting the emotion of "mile-high Denver" euphoria aside, Ronald Reagan became a great president because of his many other skills. He knew where he wanted to take our country and had the courage to stick to his beliefs.

We still don't know what Obama and the Democrats want other than George Bush back in Crawford Texas, and their party controlling both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue.

We now know the tickets: Obama-Biden; McCain-Palin.

Biden is an asset as a foreign policy adviser. Palin will be an asset on domestic and energy issues. All have compelling stories. But ultimately this race is about McCain's experience and world view and Obama's ability to excite his base.

We have one more exciting convention (now with a new player in Gov. Palin) and then 60-plus days to go at full speed. The winner gets the toughest job in the world with the most difficult agenda we as a nation have faced in decades.

The Perfect Stranger

By Charles KrauthammerWASHINGTON -- Barack Obama is an immensely talented man whose talents have been largely devoted to crafting, and chronicling, his own life. Not things. Not ideas. Not institutions. But himself.

Nothing wrong or even terribly odd about that, except that he is laying claim to the job of crafting the coming history of the United States. A leap of such audacity is odd. The air of unease at the Democratic convention this week was not just a result of the Clinton psychodrama. The deeper anxiety was that the party was nominating a man of many gifts but precious few accomplishments -- bearing even fewer witnesses.

When John Kerry was introduced at his convention four years ago, an honor guard of a dozen mates from his Vietnam days surrounded him on the podium attesting to his character and readiness to lead. Such personal testimonials are the norm. The roster of fellow soldiers or fellow senators who could from personal experience vouch for John McCain is rather long. At a less partisan date in the calendar, that roster might even include Democrats Russ Feingold and Edward Kennedy, with whom John McCain has worked to fashion important legislation.

Eerily missing at the Democratic convention this year were people of stature who were seriously involved at some point in Obama's life standing up to say: I know Barack Obama. I've been with Barack Obama. We've toiled/endured together. You can trust him. I do.

Hillary Clinton could have said something like that. She and Obama had, after all, engaged in a historic, utterly compelling contest for the nomination. During her convention speech, you kept waiting for her to offer just one line of testimony: I have come to know this man, to admire this man, to see his character, his courage, his wisdom, his judgment. Whatever. Anything.

Instead, nothing. She of course endorsed him. But the endorsement was entirely programmatic: We're all Democrats. He's a Democrat. He believes what you believe. So we must elect him -- I am currently unavailable -- to get Democratic things done. God bless America.

Clinton's withholding the "I've come to know this man" was vindictive and supremely self-serving -- but jarring, too, because you realize that if she didn't do it, no one else would. Not because of any inherent deficiency in Obama's character. But simply as a reflection of a young life with a biography remarkably thin by the standard of presidential candidates.

Who was there to speak about the real Barack Obama? His wife. She could tell you about Barack the father, the husband, the family man in a winning and perfectly sincere way. But that only takes you so far. It doesn't take you to the public man, the national leader.

Who is to testify to that? Hillary's husband on night three did aver that Obama is "ready to lead." However, he offered not a shred of evidence, let alone personal experience with Obama. And although he pulled it off charmingly, everyone knew that, having been suggesting precisely the opposite for months, he meant not a word of it.

Obama's vice presidential selection, Joe Biden, naturally advertised his patron's virtues, such as the fact that he had "reached across party lines to ... keep nuclear weapons out of the hands of terrorists." But securing loose nukes is as bipartisan as motherhood and as uncontroversial as apple pie. The measure was so minimal that it passed by voice vote and received near zero media coverage.

Thought experiment. Assume John McCain had retired from politics. Would he have testified to Obama's political courage in reaching across the aisle to work with him on ethics reform, a collaboration Obama boasted about in the Saddleback debate? "In fact," reports the Annenberg Political Fact Check, "the two worked together for barely a week, after which McCain accused Obama of 'partisan posturing'" -- and launched a volcanic missive charging him with double cross.

So where are the colleagues? The buddies? The political or spiritual soul mates? His most important spiritual adviser and mentor was Jeremiah Wright. But he's out. Then there's William Ayers, with whom he served on a board. He's out. Where are the others?

The oddity of this convention is that its central figure is the ultimate self-made man, a dazzling mysterious Gatsby. The palpable apprehension is that the anointed is a stranger -- a deeply engaging, elegant, brilliant stranger with whom the Democrats had a torrid affair. Having slowly woken up, they see the ring and wonder who exactly they married last night.

Biden Wanted to Break Up Iraq

At the Democratic convention, Joe Biden had the opportunity to showcase his foreign policy experience. Yet his principal and most recent foreign policy initiative -- his plan for the soft partition of Iraq -- was glaringly absent from his acceptance speech. When Barack Obama named his running mate, he ticked off Mr. Biden's work on a range of other foreign policy issues -- from chemical weapons to Bosnia. But there was no mention of Mr. Biden's plan for Iraq.

This was a remarkable omission. Mr. Biden's Iraq plan had been a central theme of his own presidential campaign, and the subject of numerous addresses, television appearances, and op-eds. He authored a Senate resolution, passed in September, that reflected his plan, and he even created a Web site to promote it: www.planforiraq.com. But there is no more talk about that Senate resolution. And the Web site has been quietly taken down.

Why the sudden silence?

![[Biden Wanted to Break Up Iraq]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/ED-AI139_Senor_NS_20080828185711.jpg) |

| David Klein |

When Mr. Biden first proposed his plan with much fanfare just over two years ago, it was greeted with deep concern by a number of Iraqi political leaders. They loosely understood the Biden plan to mean a Kurdish state in the provinces north from Mosul up to the Turkish and Iranian borders; a Shiite state in the provinces south of Baghdad down to the Kuwaiti border; and a Sunni state in the provinces immediately north and northwest of Baghdad.

Mr. Biden was well known to Iraqi leaders. He had visited Iraq more than other Senate critics of the Bush administration. As a supporter of the war and later as a pivotal voice on the early congressional funding debates, he had been constructive in his criticisms. For those of us advocating for increased troop levels early on, Mr. Biden was an ally. Indeed, even before the war, he said on the Senate floor that "we must be clear with the American people that we are committing to Iraq for the long haul; not just the day after, but the decade after." And despite his reputation for lecturing, he actually would listen to U.S. officials on the ground.

His case for soft partition was based on the Bosnian model where, he argued, the U.S.-brokered Dayton accords had "kept the country whole by, paradoxically, dividing it into ethnic federations." There was a logic to it. Unlike post-World War II Germany and Japan, both Bosnia and Iraq had disparate ethnic and sectarian communities; both were modern creations, established out of the ashes of the Austrian and Ottoman Empires, respectively.

But that is where the similarities ended. As a model for a tripartite federation of secure, semi-independent regions, Bosnia offered few actionable lessons for us in Iraq.

First, the 1995 Bosnia peace agreement was possible only after the momentum in the Balkan war had turned markedly against the Serbs. Until then, the Serbs had been on offense, were successful, and had no incentive to compromise. But by the mid-'90s, the Serbs suddenly found themselves defeated, with no viable alternatives to cutting a deal.

When Mr. Biden was arguing for a similar plan for Iraq, however, the Sunni extremists -- al Qaeda in Iraq, the 1920s Revolutionary Brigades, and other members of the Sunni resistance -- were in ascendance. So were the Shiite extremists, including Moqtada al-Sadr's Mahdi Army and the Islamist Badr Brigades. The radicals had not been defeated.

Second, the key leaders behind the Bosnian war were in a position to sign a deal and deliver their proxies. Who would Mr. Biden have proposed we bring to the table to negotiate on behalf of the Sunnis and Shiites? Did he have confidence that they would be able to rein in the militias? The Shiite political leadership in Iraq's Parliament, for example, had very little influence over the Sadrists, whose movement was growing and whose leader had national -- not regional -- ambitions. Meanwhile, moderate Sunni leaders were losing hearts and minds in Sunni dominated areas to a violent campaign of intimidation by jihadists.

Third, the Bosnian leaders knew that the U.S. and its NATO allies were committed to enforce any settlement with a long-term military presence. NATO had dedicated some 100,000 troops to Bosnia and Kosovo. As senior Clinton administration diplomat James Dobbins has pointed out, in Bosnia the ratio of civilians to occupation military forces was 50 to 1. Around the time that Mr. Biden was pushing his partition proposal, the approximate civilian-to-military ratio in Baghdad alone was 700 to 1. Our presence was virtually invisible. And, even worse, Mr. Biden's proposal would have begun a phased redeployment of U.S. troops in 2006 and withdrawn most of them by the end of 2007. He argued that his plan would require fewer troops in the immediate future, whereas Bosnia demonstrated just the opposite.

Fourth, by the time the Bosnian leaders had met at Dayton, the former Yugoslav republic had already been carved into ethnic enclaves through years of civil war. The contours for partition were a reality on the ground. They just needed to be finalized at Dayton. In Iraq, while some two million Iraqis had fled at the time of Mr. Biden's proposal and another two million were internally displaced, millions more would have been uprooted and forced to relocate. Almost a quarter of the remaining population, some five million Iraqis, still lived in mixed neighborhoods. As the International Crisis Group's Joost Hiltermann (a critic of American policy in Iraq) explained at the time, "the geographic boundaries do not run toward partition at all. There is no Sunnistan or Shiastan. Nor can you create them given the highly commingled conditions in Iraq, where people remain totally intermixed, especially in the major cities."

Fifth, the regional neighbors in the Balkans ultimately supported the Dayton accords. But a Bosnian solution in Iraq could have easily invited hostilities from Turkey or Iran, both of which have their own Kurdish minorities. If a semi-independent Kurdistan in northern Iraq were to embolden other Kurdish communities nearby or serve as a harbor for their operations, it could quickly destabilize borders.

At the time he was promoting his plan, Mr. Biden would rhetorically challenge any critic to come up with their own plan if they didn't like his. He would repeat his formula as though there were no other path. His frustration was understandable -- by the end of 2006, we were on the verge of complete failure, as sectarian violence had surpassed al Qaeda and the insurgency as the principal threat to Iraq. But his analysis was incorrect.

In 2007, the U.S. military showed that there was another option. The Bush administration finally decided upon a comprehensive counterinsurgency strategy, based on providing basic security for Iraqi civilians, and backed by a surge of troops to support it. The new strategy has paid large dividends against al Qaeda, Sunni insurgents and Shiite militias. Iraqi deaths due to ethnosectarian violence have declined by approximately 80% over the past year. U.S. casualties are at record lows.

While there's still work to be done, reconciliation can be seen today across Iraqi society. In the Iraqi Army, for example, the First Brigade of the First Division is 60% Sunni, 40% Shiite. This mixed brigade has fought in Anbar province against Sunni al-Qaeda terrorists, as well as in operations in Basra against the Shiite Sadrist militia. The sectarian mix, cohesion and effectiveness of the First Division's First Brigade is increasingly reflected throughout Iraq's national army. Mr. Biden has never explained whether the relevance of his plan has been eclipsed by these nonsectarian trends.

In response to critics who charge that he lacks experience, Mr. Obama has argued that he has something more important: judgment. What was Mr. Obama's judgment about his running mate's plan for Iraq? How would he have gone about implementing it if the two men were in charge at the time? And if they now believe that Mr. Biden's signature plan was a mistake, should they acknowledge that in a more serious way than by simple omission?

Mr. Senor is an adjunct senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and a founder of Rosemont Capital. He served as a senior adviser to the Coalition in Iraq and was based in Baghdad in 2003 and 2004.

No comments:

Post a Comment