The Sky Isn't Falling

The Sky Isn't FallingIn this column I often take a skeptical look at liberal scare-mongering about global warming and cancer threats from pesticides, Teflon frying pans, plastic bottles, cell phones, etc. The liberal scaremongers' solution is always: more government.

But conservatives scare people, too.

When I was growing up, most everyone agreed that it would be a terrible thing if young people were exposed to sex. It must be kept out of sight.

When an obviously pregnant Lucille Ball appeared on "I Love Lucy," it was a controversial television breakthrough. Yet the word "pregnant" was never uttered. Simply saying the word was taboo.

When I was 11, the innocent movie "Pillow Talk" was attacked because Rock Hudson and Doris Day argue about "bedroom problems". Reviews said, it "comes close to the forbidden border."

Today, parents would be relieved to find their kids watching "Pillow Talk." The PG movie "Hairspray" features a flasher and jokes about teen pregnancy. Sex is a regular storyline on "family" TV shows.

This is terrible for kids, says Peter Sprigg of the Family Research Council.

"They are being exposed to sex and to talk about sex before they're even old enough to even think about having sex," he told me in my recent "20/20" special "Sex in America".

"Young people who watch a lot of sexual content on television have distorted attitudes about sexuality. That it must be that everybody's who's not married is going around having sex all the time and having kinky sex in all kinds of strange situations."

Complaints from groups like Sprigg's inspire politicians to make noises about "protecting" America by banning such sex from the public square, even if it means legislating some of our liberty away. Sen. Joe Lieberman promised action to stay "the rising tide of sex, violence and vulgarity," which he says "has coarsened our culture."

Our culture has become coarser. Young people swear loudly in public, have vulgar tattoos and wear jeans that keep getting lower. Advertising shoves sex in our faces.

In fact, today, sex is more pervasive than my parents ever imagined it could be.

Sprigg says it's a reason for problems like "the rise of sexually transmitted diseases [and] the increase in out-of-wedlock pregnancies and births."

But where is that increase in out-of-wedlock births, etc.? We were surprised to find that although STDs are up and the '60s sexual revolution brought an increase in teen pregnancy, over the past 10 to 15 years, the rape rate, the divorce rate and the percentage of teens having premarital sex have steadily declined.

I told Sprigg the good news.

"I'm not sure I accept the premise that negative effects aren't happening," he said.

Sometimes Sprigg's group reaches far to make a point. It issued a press release lamenting bad news from the Centers for Disease Control about an increase in out-of-wedlock teenage pregnancies.

But that increase was a one-year aberration from the 10-year trend. I told Sprigg his release was deceitful.

His answer was telling: "It has been going down, and the rate[s] of out-of-wedlock births and of teen births have been going down. But until they go down to zero, we have to keep trying to promote these positive values in our culture."

I assume many people reading this agree with Sprigg. After my TV special, I got hateful e-mail: "Stossel you are disgusting. ... " "[Your TV show] added fuel to the fire for the demise of our society."

But let's be realistic, says family therapist Dr. Marty Klein, author of "America's War on Sex". Sex isn't going away, and it's not poisoning our culture.

"The truth is, children think about sex whether we want them to or not. There are groups of people out there who are devoted to scaring the heck out of Americans. ... I think it makes some people feel good because they say, aha, there's the enemy, and if only we could do something about that, everything would be better."

The truth is, "doing something" means more government. And more government doesn't make life better. If government leaves us alone, we will survive crude sex in the public square.

The way forward for Fannie and Freddie

By Lawrence Summers

Anyone who cares about the health of the US economy should welcome the enactment of the Treasury’s rescue plan for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, along with other measures to support the housing market. While there is room for argument about details, the risks to the financial system were too great to allow delay.

No one should suppose, however, that the issue is now satisfactorily resolved, even for the short term. Emergency legislation was necessary because market participants were unwilling to buy Fannie and Freddie’s debt; investors doubted that the government-sponsored enterprises were healthy enough to repay it and did not draw sufficient reassurance from the implicit guarantee of federal support. If their debt proves easier to place now, it is only because this guarantee has been strengthened, not because anything has changed at the GSEs.

This, to put it mildly, is a highly problematic posture for policy. While I strongly supported the Federal Reserve’s policy response to the crisis at Bear Stearns because it was necessary to avoid systemic risk, it is easy to sympathise with those who fear that bailouts inhibit market discipline. Consider how much more problematic the Bear Stearns response would have been had policymakers signalled their commitment to back the company’s liabilities without limit; left management in place with no change in the business model; and allowed dividends to be paid and shareholders to keep going with hope for a better tomorrow. Yet all of these elements are present in the cases of Fannie and Freddie.

To see the temptation and danger inherent in a situation of this kind, one need only look back to the mismanagement of the savings and loans crisis during the 1980s. Policymakers protected depositors, allowed institutions to operate even when their fundraising depended on government support, and suspended regular standards in order to attract private capital. With gains privatised and losses socialised, taxpayers ultimately ended up with a $300bn-plus bill measured in today’s dollars.

Allowing the clearly undercapitalised GSEs to continue operating within their current paradigm carries similar risks. The principal difference is that the GSEs are much larger than the thrift institutions, while the housing crisis is more serious than anything we have seen since the Depression.

To be sure, if one supposed that the GSEs’ problems were all issues of confidence and was certain of their underlying financial health, there might be a case for government guarantees with no onerous conditions. But almost every outside observer agrees that pre-crisis, the GSEs could only borrow because of their implicit government guarantees. Since the crisis their position has sharply deteriorated, and will deteriorate further.

There is no question that we need the GSEs to be highly active in support of the housing market and financial system in the months ahead. If the authorities can see a path to their being able to play such a role in a framework where it can honestly be said that their borrowing is based on confidence in their financial position rather than primarily on federal guarantees, then this is obviously the preferred alternative. But after what we have seen, such a judgment cannot be based on the GSEs’ own claims, the understandable desire of government officials to maintain confidence and attract private capital, or the fact that they are able to borrow – which only reflects the strength of federally provided credit assurances.

If this preferred alternative is, as I fear, not realistic given the state of GSE finances, the government should use its new receivership power to protect taxpayers and the financial system. In the process, payments to stock holders, holders of preferred stock and probably subordinated debt holders would be wiped out, conserving cash for the benefit of taxpayers. The GSEs’ borrowing costs would fall considerably, helping prospective homeowners.

In this scenario, the government would operate the GSEs as public corporations for several years. They would then be in a position to extend credit where appropriate to support resolution of the current housing crisis. Once the crisis has passed, the federal government would divide their functions into government and private components, the latter of which would be sold off in multiple pieces. The proceeds could be used to fund the low-income housing support activity that was previously mandated to the GSEs.

With this approach, the federal government would be in a position to support the housing market in the years ahead without encouraging dubious financial practices or denying financial reality, as is the case today. In the longer term, it would provide an opportunity to rebuild the housing finance system on far stronger foundations.

A major concern is that receivership would endanger the financial health of the US by taking on to the federal government’s balance sheet all the liabilities of the GSEs. This argument confuses appearance with reality. Recent statements by the Treasury and the Fed have removed any doubt that the US will stand behind the senior debt of the GSEs. Surely everyone should have learned by now that keeping liabilities off balance sheets does not make them any smaller or less real.

The stakes here are high. The choices made in the coming months will bear on the housing market, future taxpayer burdens, the credibility of US financial authorities in times of crisis and the integrity of the political system. It is a time for decisive action.

The writer is Charles W. Eliot university professor at Harvard and a managing director of D.E. Shaw & Co

Disappointing results weigh on Wall Street

By Jeremy Lemer in New York

Wall Street stocks fell back modestly yesterday in a muted session of trading after a number of disappointing earnings reports from the likes of Freddie Mac and Whole Foods.

Freddie Mac shares plunged 10.8 per cent to $7.17 after the mortgage-finance company posted its fourth loss in a row and said it would cut its dividend.

Fannie Mae, another government sponsored entity, slumped 7.7 per cent to $12.56 on the news. Fannie reports results on Friday.

Elsewhere in the financials sector the news was mixed but the sector was among the biggest losers of the morning session, dropping 0.7 per cent.

Ambac Financial, the beleaguered bond insurer, recorded a second-quarter profit but excluding certain gains due to accounting changes the company lost far more than expected. Ambac shares, which have lost over 90 per cent of the value in the last year, rose 9.1 per cent to $5.16.

Marsh & McLennan, said second-quarter profit fell 63 per cent to $65m due to higher staff costs and certain writedowns at its corporate security division. The insurance broker still beat analyst’s estimates and the shares rose 4.3 per cent to $30.60.

For the most part financials have had another torrid quarter.

Melissa Roberts, an analyst at KBW, said: “Results continued to be disappointing across capitalisation levels [revealing] continued asset quality deterioration, revenue growth offset by mounting expense growth, and reduced profitability.”

KBW cut its earnings estimates for 2008 and 2008 by 14 per cent and 10 per cent respectively as a result.

Volatile oil prices, profit taking and some poor results took their toll on the consumer-facing stocks that were among the strongest gainers on Tuesday.

Whole Foods, the grocer, tumbled 15.9 per cent to $19.28 after it posted annual earnings that undershot analyst’s estimates.

The company said net income slumped 31 per cent to $33.9m and added that it would cut the number of planned store openings over the year.

As a whole, the consumer discretionary and staples sectors lost 1.4 per cent and 0.4 per cent respectively.

By lunchtime in New York, seven of the 10 leading industry groups were in the red, knocking the benchmark S&P 500 index down 0.2 per cent to 1,282.15 points. The Dow Jones Industrial Average dipped 0.2 per cent to 11,597.45. The Nasdaq Composite rose 0.4 per cent to 2,358.36.

On Tuesday stocks rose the most in four months after oil prices dropped sharply and the Fed Reserve kept its benchmark interest rate at 2 per cent. An accompanying statement seemed to reduce the likelihood of rate rises going forward soothing investors concerns.

In the telecoms sector, disappointing earnings news dragged the sector down 2 per cent on Wednesday. Sprint Nextel posted a $344m second-quarter loss due to spending on discounts and advertising to win new customers. Sales fell 11 per cent to $9.06bn and the shares dived 9.9 per cent to $7.70.

Qwest Communications International said profit dropped 24 per cent to $188m and cut its annual forecast. The results were in line with estimates and the shares slipped 3.3 per cent to $3.47.

There was some good news amongst the welter of results data. Cisco climbed 6.4 per cent to $24.10 after posting estimate-beating fourth-quarter profits and reaffirmed its short-term sales projections calming fears that the business environment is weakening

Microsoft also received a boost after an analyst at UBS recommended buying the stock on the basis that the company could buy back up to $20bn of company stock over the next three months.

Any buyback would offer some consolation to shareholders for Microsoft’s botched efforts to buy Yahoo, the internet search company, and the shares rose 2.1 per cent to $26.76. The reports lifted the broader sector 0.7 per cent.

Materials stocks were the biggest gainers, climbing 1.2 per cent on some analyst upgrades and a small bump in certain commodity prices.

Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold was the outstanding performer, adding 9.3 per cent to $86.31.

Citigroup analyst John Hill advised clients to buy the shares noting that they had dropped more than 35 per cent since mid-June while the company still had exposure to China, high margins and strong free cash flow.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2008

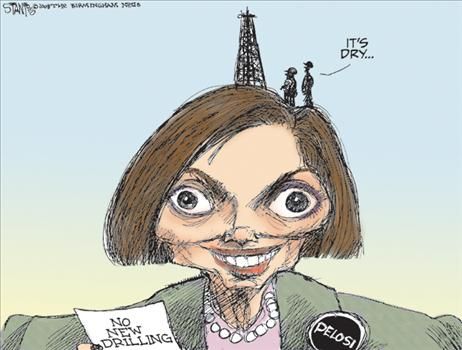

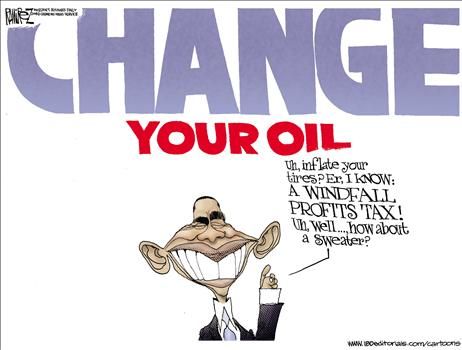

Politics and petrol

Forget Iraq, forget global warming. The soaring price of oil, and the cost of filling a car with petrol, have concentrated the minds of cash-strapped US voters. It has pushed energy to the front of an increasingly fractious debate between John McCain and Barack Obama, Republican and Democratic presidential contenders. Both men have tried to win support with populist gestures, be they petrol tax relief or a windfall levy on oil companies. A more rounded approach is needed.

Several inconsistencies lie at the heart of the Obama-McCain debate. They both acknowledge the need for the US to become less reliant on foreign oil imports and improve energy efficiency. They back a cap-and-trade system for limiting carbon dioxide emissions, an essential step for putting a cost on pollution. But it is hard to know whether the next president will curb energy use or subsidise it and whether America wants to punish oil companies with heavier taxes or liberate them by relaxing long-standing curbs on oil exploration.

The Democratic approach is to blame “big oil” and futures markets for the intolerable rise in pump prices, a strategy that has popular resonance. But, in pandering to anti-business sentiment, Mr Obama risks undesirable consequences. His proposal to tax the oil companies’ windfall profits is likely to drive prices higher if producers defer investment in response. His party’s efforts to impose limits on oil and natural gas futures trading have displayed basic ignorance about the causes of market tightness.

Mr McCain is being unrealistic if he believes the US can achieve energy independence by 2025. It will remain a net importer for decades. His offer, too, of a petrol tax holiday in the summer driving season is tantamount to subsidising demand and would support prices.

But his proposal to lift curbs on domestic offshore oil exploration, to which Mr Obama is opposed, is long overdue. The economics of deep-water drilling have become more attractive and the willingness of assertive producers such as Venezuela to flex their muscles over energy provides every incentive to raise domestic output.

To criticise Mr McCain for being in the “pocket of big oil” misses the point. His bigger mistake is to think his policies can bring prices down soon. They will not. A courageous leader would admit that. The Republican package, while far from perfect, includes an essential expansion of civil nuclear power, which Mr Obama supports only conditionally, and alternative energy investment. It is a broader set of long-term answers to US energy problems.

US banks urge sweeping credit market reform

By Aline van Duyn in New York

The world’s largest banks are proposing dramatic revisions to the securitisation and derivatives industries, which will bring large swathes of these markets into regulators’ sights and could limit the size of the future investor base for complex financial products.

The proposals are the result of a study of the financial crisis, headed by Gerald Corrigan, former head of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and managing director at Goldman Sachs, and published on Wednesday.

Its conclusions – backed by banks and investment banks including JPMorgan, Merrill Lynch, Citigroup, HSBC, Lehman Brothers and Morgan Stanley – are further evidence that the credit crisis could have lasting effects on the financing methods that were at the heart of the credit bubble.

Writedowns at financial institutions following the slide in house prices and surge in foreclosures on subprime and other mortgages have already reached close to $500bn.

“The fact that financial excesses fundamentally grow out of human behaviour is a sobering reality, especially in an environment of intense competition between large integrated financial intermediaries which, on the upside of the cycle, fosters risk taking and on the downside, fosters risk aversion,” says the 170-page report, which is titled Containing Systemic Risk: The Road to Reform.

It contains numerous recommendations aimed at curbing excessive risk-taking at financial institutions, including support for accounting reforms aimed at bringing off-balance sheet exposures on to balance sheets and devising new criteria for “sophisticated investors”, which would probably result in a smaller investor base.

For example, under the new criteria, auction-rate securities – a $330bn structured bond market widely used by municipalities and student loan providers to raise funds – would not probably be marketed to retail investors.

As well as signalling unprecedented support from the biggest financial institutions for rules governing their behaviour, the Corrigan report does much to dispel the previously widely-held views that financial risks could be quantified, measured and controlled.

“Risk management is more of an art than a science,” Mr Corrigan says.

The most specific recommendations centre around the credit derivatives market, which has grown to $62,000bn of outstanding contracts in a matter of years.

Many of these changes – which have also been urged by the New York Fed – will be expensive. They include the creation of a clearing house and investments in technology to confirm and settle trades and determine exposures rapidly.

The commitments “may require market participants to make costly investments in infrastructure (human capital and technology) and change business processes, and accept changes to market practices, that in the past have generated sizeable revenues but at the cost of weakening the underlying foundation of the markets,” the report says.

“Costly as these reforms will be, those costs will be minuscule compared to the hundreds of billions of dollars of writedowns experienced by financial institutions in recent months, to say nothing of the economic dislocations and distortions triggered by the crisis,” the report adds.

Although the current credit crisis has its roots in mortgages and the boom in mortgage-backed securities, the scale of the over-the-counter credit derivatives markets has contributed to the contagion.

The near-collapse of Bear Stearns in March highlighted these risks, as the Wall Street investment bank was connected to all leading financial institutions through the many over-the-counter trades it had entered into.

Such counterparty risk could be reduced by the establishment of a clearing house for credit derivatives, a move planned by the end of the year. It would, for the first time, bring such a large OTC market firmly in the sights of regulators.

Mr Corrigan and the New York Fed had previously started to try to curb systemic risks, aiming to reduce the backlog in settlement and confirmation of trades. However, these efforts have not kept up with the growth of the market, and the industry has now committed to a fresh round of ambitious targets to boost the infrastructure and safety of these markets.

America's next president

A leftie bent

A sinister aspect of the presidential campaign

WHETHER Barack Obama or John McCain triumphs in November, the victor will be the eighth left-handed president of America. While making up just 10% of the general populace, 18% of American presidents have been lefties, perhaps given extra drive by centuries of persecution. Of the past six presidents, four have been cack-handed. Left-handedness was traditionally regarded as an unnatural aberration—“sinister” is derived from the Latin for left and the word “left” itself comes from an Anglo-Saxon term for “weak” or “broken”. Ronald Reagan was one of many southpaws forced to write with the “right” hand.

The Fed

More worried about growth

The Fed suggests that growth is now as big a worry as inflation

IN THE past month, a worsening economic outlook, renewed financial turmoil and a big drop in oil prices have all made the Federal Reserve’s anti-inflation rhetoric seem increasingly out of place. The central bank on Tuesday August 5th acknowledged as much, in effect postponing again the date at which it can start to raise interest rates.

“Although downside risks to growth remain, the upside risks to inflation are also of significant concern,” America’s central bank said at the conclusion of Tuesday’s policy meeting. The news was in what it did not say: it dropped the assessment of its statement on June 25th, that downside risks to growth had “diminished somewhat.”

The optimism in June reflected the Fed’s belief that its job of cushioning the economy from the credit crisis was nearing completion and it could turn its focus to inflation and deciding when to start raising its short-term interest rate target from the current 2%.

That view was rapidly overtaken by events. The failure of IndyMac, a mid-sized bank, and a sudden loss of investor confidence in the big quasi-public mortgage agencies, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, convulsed markets. A pledge by the Treasury Department and the Fed to back up the two agencies’ borrowing ensured that neither would founder, but they are likely to become even more reluctant to expand their backing of American home mortgages. That is another blow to the moribund housing market, which had shown signs of stabilising.

The Fed’s statement on Tuesday should not have come as a surprise. Ben Bernanke, the chairman, had signalled a renewed concern about the outlook in testimony in July. Only last week the Fed announced that it was expanding and extending some of its liquidity programmes in light of “continued fragile circumstances in financial markets.”

But confusion about the central bank’s priorities has persisted because it has coupled such statements with a continuing drumbeat of concern about inflation. Lou Crandall, chief economist at Wrightson ICAP, a money-market research firm, says the Fed has a “conviction vacuum.” In fact, the Fed has been unclear whether growth or inflation would dominate its decision-making for the rest of the year because the data on both are dreadful.

The confusion has begun to lift. The inflation outlook has improved since June: commodity prices (most importantly oil) have dropped and measures of inflation expectations have improved. The unemployment rate rose to 5.7% in June, up a full percentage point since November and well above most estimates of the natural rate of unemployment, below which inflation tends to accelerate. And with the economy not expected to grow much in coming quarters (it may even shrink), downward pressure is likely on wages and inflation.

The Fed’s statement did not short-change inflation worries this week, of course: “Inflation has been high…some indicators of inflation expectations have been elevated.” But by putting these developments in the past tense, the Fed indicated that the news has stopped getting bad. Moreover, even that degree of concern may not be widely shared. That it found its way into the statement may reflect Mr Bernanke’s efforts to mollify hawkish members of the Federal Open Market Committee who might otherwise have joined repeat dissenter Richard Fisher, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, in voting against the decision. Elizabeth Duke, a former banker who was sworn in just before the meeting started, was one of the ten officials voting in favour.

No comments:

Post a Comment