By

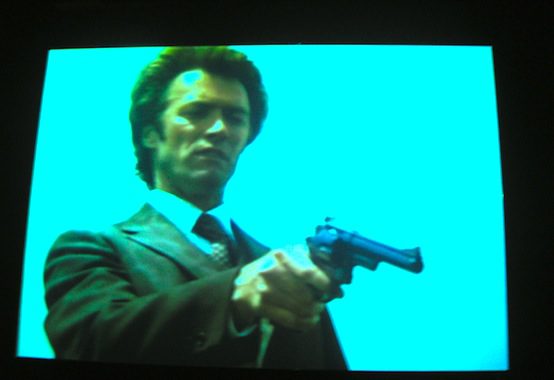

One nugget of information I did not feel it necessary to include in my self-introduction to TAC readers is that I’m a huge Clint Eastwood buff. Not so much anymore, but as I kid — and I’m talking my preteen years here — I spent an untold number of hours watching Eastwood movies. With no knowledge of film history or awareness of elite criticism, I loved all of them. I loved the Dirty Harry franchise. I loved the orangutan comedies. I loved that awful period flick with Burt Reynolds. I loved the Westerns, and not simply the well-known ones, like The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly and The Outlaw Josey Wales. I loved the Westerns that today you’d charitably call marginalia — Coogan’s Bluff, Hang ’Em High, Joe Kidd, and Two Mules for Sister Sara, etc.In a tweet last night, Ross Douthat opined that Eastwood is an overrated filmmaker who “specializes in handsome, well-executed mediocrity.” I’m okay with that. But this is a bad thing only if you judge Eastwood against his reputation as a prestige filmmaker, which began with 1992’s Unforgiven and reached its high water mark with 2004’s (truly overrated) Million Dollar Baby.

But I never saw Eastwood as a prestige filmmaker. To use a baseball metaphor, Eastwood was a workhorse pitcher — a middle-of-the-rotation guy whom you could count on to eat innings and twirl the occasional gem. Indeed, in those roughly 30 years before he became an Academy darling, Eastwood made a number of compelling genre entertainments. (Though he began directing pictures as early as 1971, it wasn’t until 1988’s Bird and 1990’s White Hunter Black Heart that Eastwood’s considerable skills behind the camera began to evince higher ambitions.) Escape from Alcatraz, it seems to me, exerted a huge influence over the more beloved The Shawshank Redemption. The supremely creepy Western High Plains Drifter and the World War II caper Kelly’s Heroes sported postmodern sensibilities that stretched the boundaries of their respective genres. Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, which helped launch the career of the young Jeff Bridges, is perhaps my favorite buddy/road movie of all time. If Firefox, in which Eastwood steals a state-of-the-art fighter jet from the Soviets, came on television right now, I’d be hard-pressed not to drop everything and waste the ensuing two hours.

All of this is longwinded prelude to the point of this post. After his surreal performance — and it was a performance, not merely a speech, was it not? — at the Republican National Convention last night, Eastwood dominated political conversation. What was the Romney campaign thinking? What was Eastwood drinking?!

I have a pet theory as to why Eastwood chose to speak. I think he felt duped by Chrysler into lending his badass gravitas to the auto bailout, and so, at least in part, he wanted to even the score.

As against those who see the last 20 years of Eastwood’s oeuvre as a renunciation of violence (from Unforgiven to Invictus to Gran Torino), my broader pet theory is that Eastwood has been a pragmatic centrist all along. Unforgiven wasn’t an about-face; there is a continuum of violence-doubting that connects Dirty Harry to Gran Torino. I wrote about this for the Washington Times in 2008, when the Harry movies were reissued in Blu-Ray format. An excerpt:

“Dirty Harry,” to be sure, embraced a rough sort of justice: As embodied by the ineffectual, defendants’-rights-conscious mayor played by John Vernon, the movie suggested post-Miranda America had entered a suicide pact with itself and given over its big cities to reprobates who could break the law and, subsequently, hide behind the law.At the RNC, Eastwood was being Eastwood: telling the truth about war in Afghanistan and succinctly making the case for firing Obama: This didn’t work; let’s try someone else.

Miss Kael noted with disgust a pivotal scene where Callahan is chastised by a San Francisco district attorney and a Berkeley criminal-rights lawyer for torturing the serial killer “Scorpio,” who had buried alive his most recent victim.

“The law’s crazy,” Callahan famously barked.

This sort of angry certitude, however, died with “Dirty Harry.” Recall the film’s grim final scene, as Callahan, having slain the dragon Scorpio, chucked his gold badge into a nearby pond (an allusion to 1952′s classic “High Noon”) — he knew he’d pushed far beyond the limits of the law.

Not here, and not later, is Harry Callahan ever pleased with dispensing violence: He is always a reluctant avenger. Each of these movies ends on a note of almost Nietzschean sorrow at the decline of moral authority.

Out of this fatalism came the equally grim “Magnum Force.”

The first sequel certainly wasn’t as compelling overall as the original. However, at least in its basic plot, it is far less straightforward than its predecessor.

Where in “Dirty Harry” Callahan chased down the almost comically evil Scorpio, in “Magnum Force” he battles a threat from within: a gang of rogue motorcycle cops who have taken the law into their own hands.

In this, I think, it was a direct rebuke to “Harry.” Despite the sinister inferences that Miss Kael, again, drew from the film — she took its vigilante villains for “homosexual Nazis” — “Magnum Force” looked into the same abyss of American urban lawlessness that “Harry” did and stood up, however reluctantly, for our system of justice.

Compare Callahan’s fuming dismissal of civil-liberty niceties in “Dirty Harry” (“the law’s crazy”) to his weary-yet-firm appraisal at the end of “Magnum Force” (“The system’s lousy, but it’s all we have”).

“The Enforcer,” with its interplay of white hippie revolutionaries and black-power charlatans, is arguably the most dated of the series. But it, too, in its way, reveals more of Callahan’s unsung complexities.

A young Tyne Daly figures in the “Enforcer’s” plot as a grossly underqualified beneficiary of the time’s latest outrage of political correctness: gender-based affirmative action. Miss Daly’s Kate Moore, who had never made an arrest in her short career, is promoted to an inspector-level slot and becomes partner to a contemptuous Callahan, who dismisses the department’s new policy as “stylish.”

Yet, gradually, Moore wins over Callahan with her pluck and earnestness — and she ultimately saves his life not once, but twice.

I’ve gone on too long. Time to check if Firefox is available via OnDemand.

No comments:

Post a Comment