The Wall Street Journal,

upon the release of the most recent annual GDP growth figure of 2% (up

from 1.3% in the previous quarter), observes: “The economy plowed ahead

at a 2% growth rate in the third quarter, which thrilled more than a few

of our liberal friends who think it’s enough to re-elect President

Obama. We’ll soon find out if they’re right, but there’s no doubt their

prosperity standards are slipping. In the third quarter of 1992, growth

came in at 4.2% (3.4% for the year) and Democrats called it a

catastrophe.”

The Wall Street Journal,

upon the release of the most recent annual GDP growth figure of 2% (up

from 1.3% in the previous quarter), observes: “The economy plowed ahead

at a 2% growth rate in the third quarter, which thrilled more than a few

of our liberal friends who think it’s enough to re-elect President

Obama. We’ll soon find out if they’re right, but there’s no doubt their

prosperity standards are slipping. In the third quarter of 1992, growth

came in at 4.2% (3.4% for the year) and Democrats called it a

catastrophe.”Even the liberal New York Times took a sober view of the anemic uptick: “Still, the pace of economic activity is short of what’s needed to substantially reduce the unemployment rate, now at 7.8 percent and also well below the level of growth typical in this stage of a recovery after a sharp downturn. What’s more, fears are growing that the economy could slow again in the fourth quarter. Companies are preparing for the possibility of steep tax increases and sharp spending cuts if Congress cannot agree on a deal to reduce the deficit after the election, a combination of factors frequently referred to as the fiscal cliff. In fact, a series of disappointing earnings reports from the nation’s biggest companies this week, along with a handful of layoff announcements from corporate bellwethers, suggest businesses have already begun to retrench.”

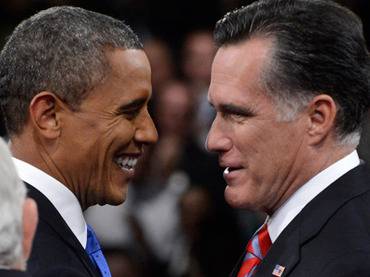

This week America will decide whether to gamble on the economic prosperity prescription being offered by Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney, or on the social equity model presented by the incumbent president Barack Obama. The contest presents as something portended in one of the wisest observations ever made by the in-certain-ways-defunct John Maynard Keynes. Previously cited in this column, it bears repeating: “Keynes, in the General Theory of Unemployment, Interest, and Money (chapter 24, part V) famously wrote: “But apart from this contemporary mood, the ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back. I am sure that the power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas. Not, indeed, immediately, but after a certain interval; for in the field of economic and political philosophy there are not many who are influenced by new theories after they are twenty-five or thirty years of age, so that the ideas which civil servants and politicians and even agitators apply to current events are not likely to be the newest. But, soon or late, it is ideas, not vested interests, which are dangerous for good or evil.”

The presidential race has focused most prominently on fiscal policy: taxing and spending. Leading economists and politicians of the Left continue to distill their frenzy from Keynes. Those of the Right seem to be in the thrall of the most visible (but, importantly, not all of the) ideas of arguably the most influential political economist of the late 20th century, Jude Wanniski.

Wanniski’s prime influence reflected his key concern, that of marginal tax rates. The battle over tax policy — dropping the top marginal rate from 70% to 28% and, later, dropping the capital gains rate –occupied the front pages of America’s leading newspapers. It dominated the macroeconomic discourse for well over a decade.

Notwithstanding dramatic tax rate reduction, by the tail end of the Clinton administration, and under George W. Bush, the world economy was plunged by a degenerating monetary policy into over a decade of economic stagnation. This columnist firmly believes that averting “taxmaggedon” — as Romney promises more credibly than does Obama — is essential to maintaining economic growth. Still, the empirical evidence — 12 years of economic stagnation — demonstrates that low tax rates are necessary but not sufficient to achieve prosperity. The need for good money, as noticed by the discerning, is the pivot upon which the possibility of prosperity turns.

The agitators of the Left, having apparently having dozed off while reading Chapter 24 of the General Theory, have developed an obsession — an idée fixe — that the primary danger to the Republic is that of the vested interests. They are fixated by the absurd notion that injuring the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of speech and the press — by muzzling corporate political spending — will somehow bring about a more equitable prosperity. They, unlike their hero Keynes, are failing to grasp that it is “ideas, not vested interests, which are dangerous for good or evil.”

The Right, meanwhile, has constituted itself as something of a cargo cult around Wanniski’s marquee prescription of low marginal tax rates. This is deeply problematic. As the Left fails to grasp its hero Keynes’s insights, the Right fails to grasp Wanniksi’s secondary prescription of the gold standard as essential to prosperity. Wanniski on gold: “This brings us at last to the monetary standard. For thousands of years, the reference point provided by gold has been the equivalent of Polaris in the world of everyday commerce. Think of each star in the sky as a different commodity or item to be “priced” in the market. This star over here is a loaf of bread of a certain weight and quality. This star is a quart of milk. … Unless civilization can agree upon one star in that galaxy, against which all other stars can be referenced, civilization could not progress much beyond the bartering of a jungle or desert commune. … Happily, many thousands of years ago, soon after the dawn of civilization, mankind fixed on precious metals as the standards for pricing. Thus, the merchant will sell one loaf of bread for 1/100th of an ounce of gold or 100 loaves for an ounce, or a Cadillac for 100 ounces. Gold money will change for smaller money in order to make smaller transactions, one ounce for twenty of silver, or 6000 of copper. But it all starts with Polaris. … As long as this one task was achieved by government, the monetary standard would remain constant.”

During the epic Wanniski epoch — including the good growth years of Reagan and of Clinton — tax policy was fought out, vividly, in the public and political sphere. Meanwhile, the monetary policy fight was relegated to the private sanctuaries of the Federal Reserve Board. Chairman Volcker and the early years of Chairman Greenspan implemented a proxy for the gold standard called the Great Moderation. And, with that, the economy grew well (and, in spurts, handsomely).

Today’s candidates for the presidency have cast next week’s vote, in large measure, as a referendum on American fiscal policy, very much including an important rear guard action over marginal tax rates. It is clear to this columnist that the election of Romney, with his dedication to relatively lower marginal tax rates, and to more sensible energy, environmental, and regulatory policy, is necessary for resumed growth. While necessary it is not sufficient.

The prospect of the restoration of 3%, or even 4%, growth depends upon an issue that appears only at the margins of the presidential race: monetary policy. Thus the possibility of yanking America out of 2% stagnation and back into prosperity currently resides in the hands of three young statesmen who, perhaps uniquely, understand that good monetary policy is the key issue at stake for growth.

Three men hold the key to American and world economic vitality. Who are they? Romney’s trusted running mate, Wanniskian Paul Ryan (guided by his excellent economist John Taylor); Rep. Kevin Brady, vice chairman of the Congressional Joint Economic Committee and author of the Sound Dollar Act; and Rep. Jim Jordan, outgoing chairman of the Republican Study Committee and staunch advocate of good monetary policy. At least two of these, and, perhaps, all three, will be installed on November 6th by the voters at battle stations in the continuing fight for an equitable prosperity.

The presidential election is, of course, of great importance. Will the voters pick the growth candidate or, discouraged, tip toward the social equity candidate? As important as is the presidency, however, the most essential battle — the fight for good money as the keystone of 4% growth with full social equity — is of even greater importance. It will be fought for where the battle belongs, in “the People’s House,” the Congress of the United States. Good money is good politics and good policy and is certain to become visible soon after the November 6th election.

No comments:

Post a Comment