Colombia’s

success in curbing the drug trade has created more opportunities for

countries hostile to the United States. What happens when coca farmers

and their allies are in charge?

Colombia’s

success in curbing the drug trade has created more opportunities for

countries hostile to the United States. What happens when coca farmers

and their allies are in charge?In the dusty town of Villa Tunari in Bolivia’s tropical coca-growing region, farmers used to barricade their roads against U.S.-backed drug police sent to prevent their leafy crop from becoming cocaine. These days, the police are gone, the coca is plentiful and locals close off roads for multiday block parties—not rumbles with law enforcement.

“Today, we don’t have these conflicts, not one death, not one wounded, not one jailed,” said Leonilda Zurita, a longtime coca-grower leader who is now a Bolivian senator, a day after a 13-piece Latin band wrapped up a boozy festival in town.

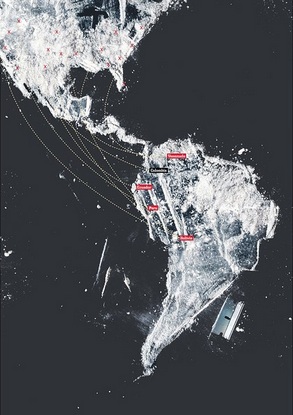

The cause for celebration is a fundamental shift in the cocaine trade that is complicating U.S. efforts to fight it. Once concentrated in Colombia, a close U.S. ally in combating drugs, the cocaine business is migrating to nations such as Peru, Venezuela, Ecuador and Bolivia, where populist leaders are either ambivalent about cooperating with U.S. antidrug efforts or openly hostile to them.

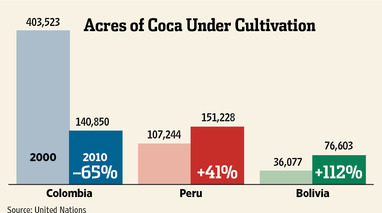

Since 2000, cultivation of coca leaves—cocaine’s raw material—plunged 65% in Colombia, to 141,000 acres in 2010, according to United Nations figures. In the same period, cultivation surged more than 40% in Peru, to 151,000 acres, and more than doubled in Bolivia, to 77,000 acres.More important, Bolivia and Peru are now making street-ready cocaine, whereas they once mostly supplied raw ingredients for processing in Colombia. In 2010, Peru may have passed Colombia as the world’s biggest producer, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Between 2009 and 2010, Peru’s potential to produce cocaine grew 44%, to 325 metric tons. In 2010, Colombia’s potential production was 270 metric tons.

Meanwhile, Venezuela and Ecuador are rising as smuggling hubs.

The trend underscores the ability of drug cartels to search out friendlier operating environments amid changes in Latin American politics. In recent years, Venezuela’s stridently anti-U.S. leader Hugo Chavez shrank the U.S. DEA’s presence there, while Bolivian President Evo Morales, himself a longtime coca grower, expelled the agency altogether. With Myanmar, they are the only countries currently “decertified” by the U.S. as failing to combat illegal drugs.

Ironically, the shift is partly a by-product of a drug-war success story, Plan Colombia. In a little over a decade, the U.S. spent nearly $8 billion to back Colombia’s efforts to eradicate coca fields, arrest traffickers and battle drug-funded guerrilla armies such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC. Colombian cocaine production declined, the murder rate plunged and the FARC is on the run.

But traffickers adjusted. Cartels moved south across the Ecuadorean border to set up new storage facilities and pioneer new smuggling routes from Ecuador’s Pacific coast. Colombia’s neighbor to the east, Venezuela, is now the departure point for half of the cocaine going to Europe by sea.

“Colombia is leaving behind its old image of the failed state in the hands of drug traffickers,” Gen. Oscar Naranjo, Colombia’s top police official, said at a Bogota news conference last year. “But evidently…that has produced a balloon effect.”

The

“balloon effect” is the idea that drug activity squeezed out of one

neighborhood or region will simply bulge into another, like air in a

balloon. For example, Mexico’s bolder efforts to confront drug

gangs—which ship cocaine made in South America to the U.S.—are pushing

gangs to the weaker states of Central America.

The

“balloon effect” is the idea that drug activity squeezed out of one

neighborhood or region will simply bulge into another, like air in a

balloon. For example, Mexico’s bolder efforts to confront drug

gangs—which ship cocaine made in South America to the U.S.—are pushing

gangs to the weaker states of Central America.In South America, the balloon effect has coincided with another phenomenon: The rise of a generation of populist leaders who view U.S. antidrug efforts as a version of the “Yankee imperialism” they disdain.

Both Venezuela’s Mr. Chavez and Bolivia’s Mr. Morales built support among mostly poor populations as staunchly anti-U.S. leaders. They describe the drug war as a facade for a strategy to control the region’s politics and natural resources, especially oil.

Mr. Chavez and other leaders say they are fighting drug trafficking. But in Venezuela, thwarting U.S. drug efforts appears to be a cause for promotion. In 2008, the U.S. declared Venezuelan Gen. Henry Rangel Silva a drug “kingpin.” This month, Mr. Chavez named Gen. Rangel defense minister.

In Bolivia, Mr. Morales, a 52-year-old Aymara Indian who took office in 2006, has spent a lifetime opposing the U.S. drug war. As the head of his country’s coca growers, he built a political movement by demonstrating against the drug police. The marches he led on the capital La Paz brought down a pro-U.S. president and paved the way for his election.

Once in office, Mr. Morales named coca growers to key law-enforcement posts, including drug czar, and has asked the legislature to expand the area for legal coca growing to almost 50,000 acres—five times the amount needed to supply Indians with chewable coca for traditional purposes.

Mr. Morales describes his policy as “Coca yes, Cocaine no,” a nod to the central role the leaves have played for centuries in Indian culture. Coca is traditionally chewed by Andean Indians as a mild stimulant. To mark the change, Mr. Morales took office in a mountaintop ceremony conducted by an Aymara Indian shaman in flowing robes.

But “Coca yes, cocaine no” turns out to be a hard ideal to follow. Valentin Mejillones, the shaman who swore Mr. Morales into office and acted as his personal spiritual guide, was arrested in 2010 with more than 500 pounds of liquid cocaine in his home. He denies wrongdoing.

Then there’s Margarita Terán, a coca grower and one-time Morales girlfriend picked to produce a section protecting coca growing for a new Bolivian constitution. In 2008, two of Ms. Terán’s sisters were caught with 300 pounds of coca paste, which is semirefined cocaine, at a police roadblock. They deny wrongdoing.

Last year in Panama, agents of the U.S. DEA nabbed Gen. Rene Sanabria, who headed a Morales anti-narcotics agency, as he was preparing to ship 317 pounds of cocaine to the U.S. Mr. Sanabria pleaded guilty and is now serving a 15-year prison sentence in the U.S.

Mr. Morales’s fiercest critics say the high-profile arrests suggest his government condones drug trafficking. Others say that his ambivalence toward antidrug enforcement has generated a level of corruption that is now out of control.

“What’s happening is that drug trafficking, amid a lack of clear policy, amid weak institutions, amid weak parties, is finding its way in,” says Juan del Granado, a former La Paz mayor and former Morales supporter who broke ranks with the president over drug policy and other differences.

The leaders blame the crime and violence in Latin America on the U.S. demand for drugs. Take Ecuador’s President Rafael Correa. When he was a child, his father, a small-time drug courier, spent time in a U.S. prison after police arrested him coming off an airplane in the U.S. with a package of cocaine.

“I lived through this, and these people are not delinquents,” Mr. Correa said in a radio address in 2007. “I do not justify what he did, but he was unemployed.”

As president, Mr. Correa ended a U.S. lease on what was then the only U.S. air base in South America, a critical post for monitoring airborne drug smuggling. He also reduced cooperation with Colombia—a move that has led to an increase in smuggling, drug analysts say—after the Colombian air force bombed a FARC encampment hidden just across the border in Ecuador in March 2008.

Even with cocaine activity expanding in other Latin nations, U.S. officials describe Plan Colombia as a success. Stable for the first time in decades, Colombia is thriving economically. Its elite, battle-tested national police now seek to spread their success by training police forces around the globe.

U.S. officials also note that Colombian coca cultivation plunged so much that total cultivation across the region is still 35% less than it was a decade ago. Still, coca plantations in Bolivia and Peru are yielding more these days, and new techniques for extracting the leaf’s active ingredients make cocaine production more efficient.

The U.S. is adjusting. In the case of the lost Ecuadorean air base, the U.S. simply leased new ones in Colombia. The DEA has stayed engaged where national politics makes it difficult, nurturing long relationships with local police commanders to produce arrests. And in a major rhetorical shift in the nearly four-decade-old Latin American drug war, American diplomats now acknowledge that U.S. demand drives the illegal drug trade. The aim is to win over leaders who are skeptical of U.S. motives.

“It’s been very good to get beyond this finger pointing, and the U.S. saying, ‘You should keep those horrible drugs out of the hands of all of our above-average children,’ ” said Gil Kerlikowske, head of the White House Office on National Drug Control Policy.

The cocaine industry has migrated before. Peru and Bolivia, where coca is legal and Indians have chewed it for centuries, were the primary source of coca leaves for a cocaine boom in the early 1980s that spawned kingpins like Colombia’s Pablo Escobar.

Then the U.S. made Bolivia and Peru the front lines of efforts to squelch drug supply. U.S. military helicopters ferried Bolivian drug police—trained, outfitted and fed by the U.S.—on coca raids. In Peru, the air force shot down airplanes suspected of carrying coca paste to Colombia in a controversial venture with the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency.

To adjust, Colombian cartels planted coca at home. By 2000, 75% of global coca cultivation had moved to Colombia, where the power of left-wing guerrillas and traffickers kept huge swaths of territory out of the state’s reach.

Today, Plan Colombia is pushing coca cultivation back to Peru and Bolivia, a round-trip journey that analysts say illustrates the difficulties of drug interdiction.

“You have the balloon effect for shifting coca production, what I call the cockroach effect for how the cartels jump from one region to the next, and then there’s the whack-a-mole policy to try to deal with all of it,” says Bruce Bagley, a political scientist at the University of Miami and an expert on the global drug trade.

For traffickers, the timing of coca’s return to Peru couldn’t be better. The country’s shoot-down policy effectively ended in 2001 after a CIA and Peruvian Air Force team mistakenly downed a plane carrying a family of U.S. missionaries misidentified as drug traffickers.

Last year, Ollanta Humala, a fervent nationalist who gets support from traditional coca-growing regions, became president of Peru. Shortly after taking office, he surprised U.S. officials by ceasing coca eradication and naming a coca-grower advocate as drug czar. Peru has restarted some eradication, but commitment to the U.S.-backed policy is widely seen as questionable.

In October, Mr. Humala’s then-cabinet chief, Salomon Lerner, said that “military” and “eradication” are “dirty words for us,” during an event at the Inter-American Dialogue think tank in Washington, D.C. (Mr. Lerner resigned recently amid a mining scandal.)

In Bolivia, the biggest challenge today may be the growing presence of international drug cartels from Mexico, Colombia and Brazil, intelligence experts say. In October, Bolivian soldiers happened upon a huge cocaine processing lab on a remote coca-growing frontier. One trafficker was killed and another was captured in a fire fight—and both were Colombian.

An internal Bolivian intelligence report obtained by The Wall Street Journal detailed the presence of Mexican, Colombian and Brazilian traffickers in the city of Santa Cruz. Meanwhile, Brazilian police say 80% of that country’s cocaine supply comes from Bolivia.

Signs of expansion are easy to find in El Chapare, a coca-growing center in Bolivia’s tropical flatland, where 90% of the harvest ends up as cocaine, by many estimates. On a recent visit, plumes of smoke and the scent of burnt wood in the muggy air signaled that locals were burning new plots for coca planting.

Workers at a local hotel warned guests not to stray from the grounds lest they happen upon a coca-processing lab nearby and startle its owners. Motorists complain that local filling stations are occasionally sold out of gasoline, which is used as a precursor in processing cocaine.

But the biggest change around El Chapare may be, ironically, the peace. For years, towns like Villa Tunari saw tense and sometimes deadly skirmishes between growers and police.

Under a new policy, coca union leaders, rather than police, enforce limits on growing. Each family member can plant one basketball-court sized “cato” of coca. U.N. figures show that Bolivia eradicated more than 20,000 acres in 2010, though the total area under cultivation remained the same.

One reason locals trim back coca farms is to maintain prices, says Ms. Zurita, the coca-grower leader. “We tell everybody you have to be smart,” she says. If everyone grows as much as they want, then it won’t be worth anything.”

Critics say that the eradication numbers are misleading. For one, older fields that have lost their productivity are being cut down to make way for new farms in pristine jungle.

That process is visible a short distance away, on the edge of one of Bolivia’s biggest Amazon reserves, where some 15,000 coca growers have cut plots into the protected land. More are expected to pour into the reserve if a major road ordered by Mr. Morales is completed. Amazon Indians who live in the park, fearing that the coca growers will damage their land and overrun their culture, have launched a movement to keep them out.

Their odds aren’t good. The president’s “loyalty is to the cocaleros [coca growers], and in reality, the cocaleros are the drug traffickers, producing coca for cocaine,” says Fernando Vargas, a leader of the Indians who is seeking to block the road. “As a result, our culture could be destroyed.”

No comments:

Post a Comment