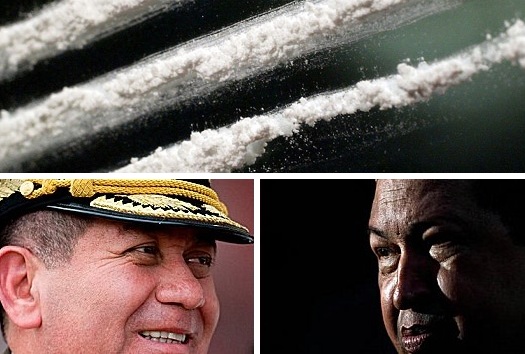

Venezuela’s

dictator Hugo Chávez was informed five years ago that his close ally

Gen. Henry Rangel Silva – the man whom he recently named Defense

Minister – is involved in cocaine smuggling.

Venezuela’s

dictator Hugo Chávez was informed five years ago that his close ally

Gen. Henry Rangel Silva – the man whom he recently named Defense

Minister – is involved in cocaine smuggling.Rangel Silva’s appointment to that key security post – coming on the heels of the return of Chávez henchman Diosdado Cabello to senior political posts – indicates that narco-generals are positioning themselves to hold on to power in spite of elections scheduled for October.

Any hope for a democratic transition this year will depend on extraordinary courage of the opposition and increased solidarity from the international community.

An official document from the archives of the Ministry of Defense, disclosed by the Miami newspaper El Nuevo Herald, shows that Chávez was notified on January 10, 2007, of “sufficient evidence linking” Rangel Silva to a November 2005 shipment of 2.2 tons of cocaine.

Rangel Silva’s involvement might have gone undetected, except for the fact that the driver of the truck carrying the contraband was his cousin, Edgar Alfonso Rincón Rangel. Efforts to prosecute Rincón and several senior military officers were apparently derailed suspiciously, suggesting a high-level cover-up.

Rangel Silva’s association with narco-trafficking is well-known. For example, the U.S. government designated him a drug kingpin in 2008, and his cordial ties to Colombian narco-guerrilla leaders were discovered in captured computer files.

The revelation in the El Nuevo Herald article is a document proving that Chávez has played a personal role in hiding the crime for years and promoting the criminal to several senior military posts.

It is no surprise that such official complicity has made Venezuela a critical hub for smuggling cocaine to Central America, Mexico, the United States, Caribbean, West Africa and Europe. This evidence confirms that Chávez has made Venezuela a narco-state.

As expected, military leaders are taking the reins of power as they learn the truth about Chávez’s mortal illness. Although civilian Chavistas or most military officers may be able to ride out a transition after their leader’s death, those involved in narco-trafficking have no “Plan B.” They either retain power at all costs or risk ending up in an orange jumpsuit a la Manuel Antonio Noriega.

Cabello’s new role as head of Chávez’s party and the National Assembly is the narcos’ insurance policy. He is a military man who commands the trust of Rangel Silva and the other kingpin soldiers.

A power struggle within the military is inevitable.

Chávez’s 13-year revolution has corrupted all of the country’s civilian institutions. He has promoted military officers based on loyalty and cemented that loyalty by cutting them in on massive corruption.

Nevertheless, on two occasions in recent years, senior officers have insisted that Chávez respect the constitution and independence of the military.

It remains to be seen whether these “institutionalists” will stand by if the narco-generals try to scuttle the election process, especially if Venezuelans take to the streets to prevent such a power grab.

The democratic opposition is unified like never before. And they think they can win power – particularly if Chávez dies or falters.

They are expected to close ranks behind a presidential nominee chosen in a February 12 primary. As the opposition gains momentum – especially if Chávez dies before the October election – Chavista hardliners and the narco-generals may make their move through stepped-up oppression or overt aggression against the democratic process.

Although the opposition is content to fight its own battle, some international solidarity should be expected – particularly if criminal gangsters attempt to deny Venezuelans the right to choose their own leader.

They will have to look for their Latin American brothers to defend the democratic process by rejecting a narco-golpe.

Although Washington appears remarkably passive now in the face of these threatening events, there is some hope that the United States will fall in behind Latin solidarity. Of course, only the United States has the muscle to demand that Chávez’s allies in Moscow, Beijing, Teheran, and Havana let Venezuelans resolve their own affairs.

If Chávez succumbs to cancer as many expect, in the next seven to nine months, a certain degree of chaos will likely ensue.

What remains to be seen is whether Venezuela’s democrats and their shy friends in neighboring countries will rise to the challenge and seek to save their country. If that does not happen, a narco-state will dig in and pose an even greater threat to all concerned.

U.S. law enforcement agencies have led the way in dealing with Chávez’s criminality, which is only part of his asymmetrical threat to our interests and security. However, unless we want to see a bad situation get worse in Venezuela, our entire national security apparatus must step up this challenge.

* Roger F. Noriega was Ambassador to the Organization of American States from 2001-03 and Assistant Secretary of State from 2003-05. He is a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and managing director of Vision Americas LLC, which represents U.S. and foreign clients, and he contributes to www.interamericansecuritywatch.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment